We wrote a piece for the Global Urban Humanities Special Issue of Room One Thousand on the transforming identity and architecture of the gaduliya lohar - nomad cart blacksmiths that wander western India. Excerpts are included here, find the full article at roomonethousand.com.

[cart blacksmiths]

The gaduliya lohar are the traditional travelling blacksmiths of southeastern Rajasthan, who identify their ancestry as weapon makers of the Rajput rulers of Mewad at Chittorgarh. When Mogul king Akbar invaded the fort, they escaped, and ashamed at the failure of their weapons, vowed never to return to Chittorgarh until Mewad was restored. This identity has carried forward to the present, and still defines them as a community. Throughout their history, they have travelled from village to village, repairing and selling farm and household tools. As cities have expanded and industrialized implements have taken the market, the competition is stiff and work has dwindled. But the draw of the city remains, and many lohar have set up camp in the city, for longer periods and with fewer caravan accoutrements, because ox carts are bulky and urban oxen are expensive to maintain. Yet they remain squatters, treated as outsiders wherever they are, because they are permanently camping, just temporary residents.

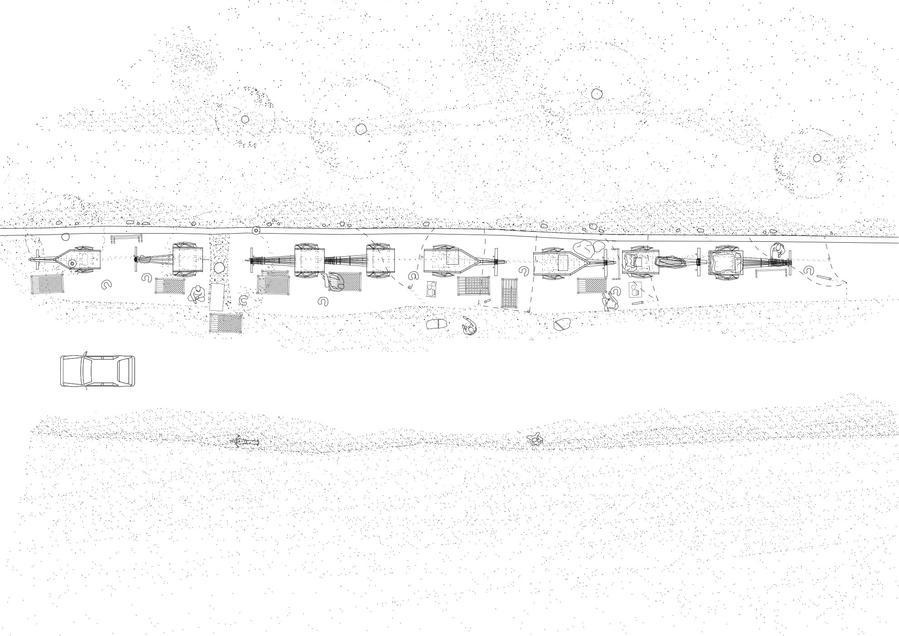

[camp system]

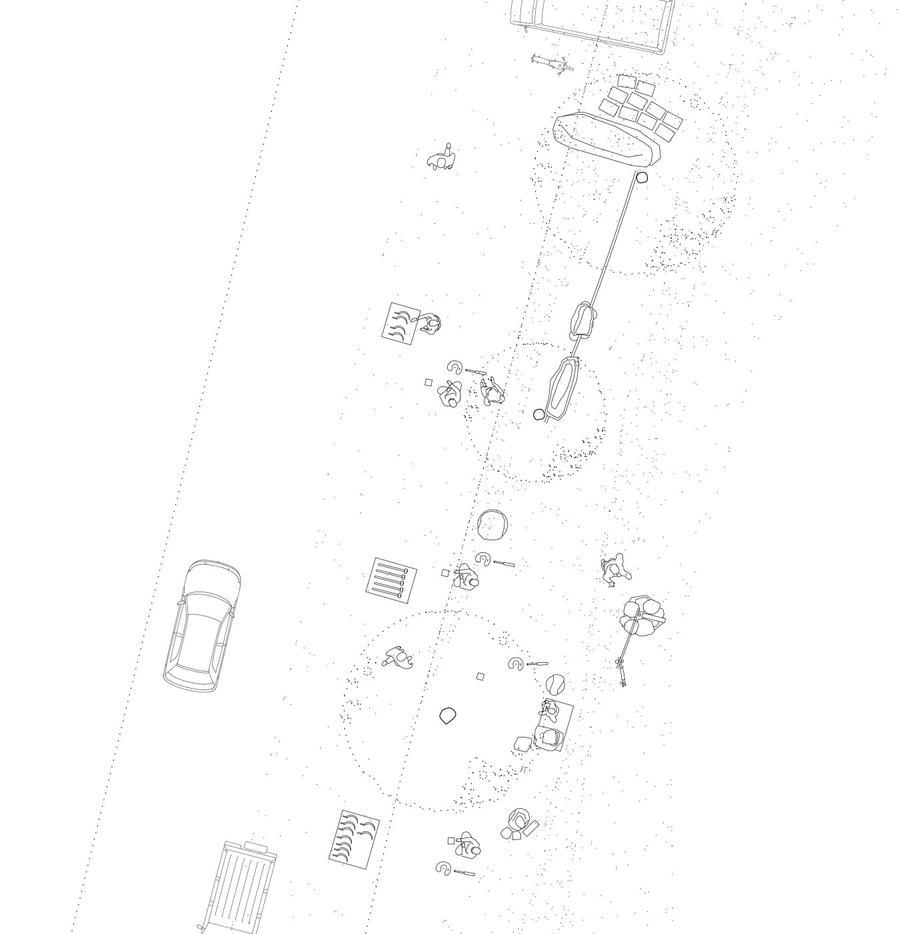

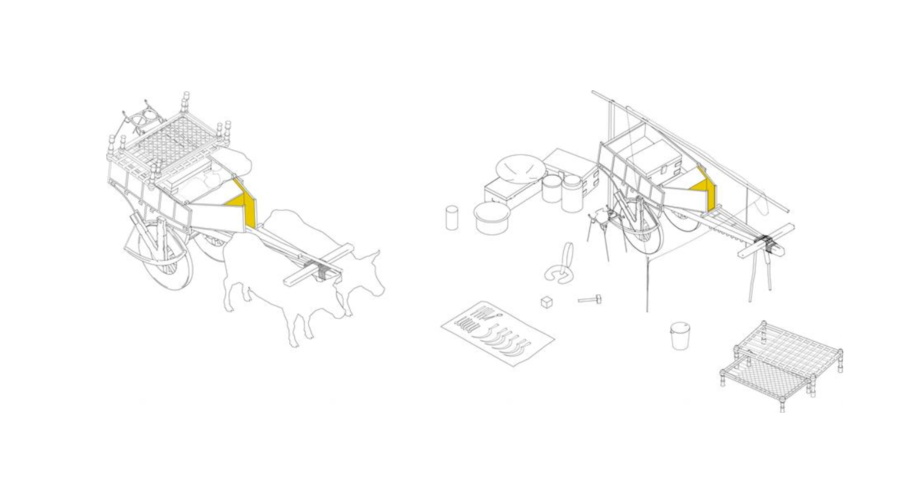

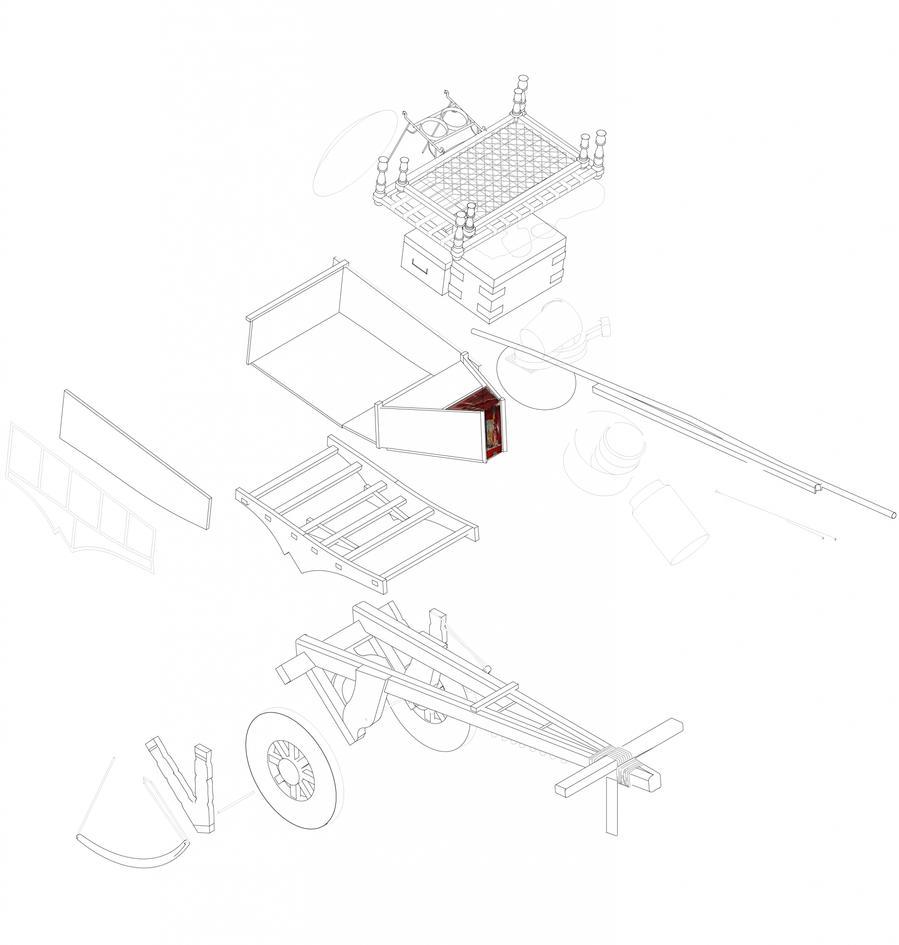

Despite their continuing inability to fit into the recognized structures of the contemporary country, the simple system they have evolved offers a potentially powerful model for the occupation of seasonal and cyclical spaces in dynamic, under-regulated, twenty-first century cities. The structure and organization of the gaduliya lohar camp is innovative in its ability to generate a complex social space on any site that fits the very basic parameters of roadside with adjacent wall, tree or fence. This capacity is built through the simple organizational structure—a string of carts lined up one by one—with a strong base element—the cart—and a tied joint that connects elements in predefined relationships carefully to certain elements and loosely to others. The organization of horizontal planes, vertical columns, inclined columns, horizontal beams and heavy wheels on a hand-molded plinth structures the ground temporarily, forms a space occupied by a group of families, and then disappears, leaving light traces behind. At once shelter, storage, sleep space and transport, the cart unfolds and refolds in a relaxed cycle, regenerating the social and physical organization of its space as it arrives in each new context.

[cart in place]

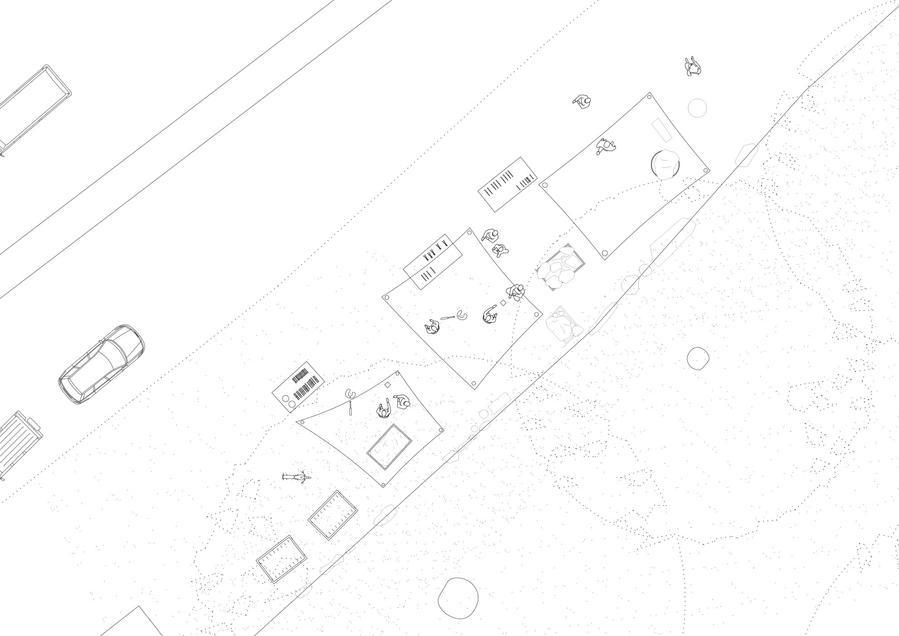

Because they move around, the gaduliya lohar are pushed uncomfortably into India’s contemporary systems of governance, which fails and ultimately they are marginalized. Without a home, without land, with a history of dependence on the goodwill of neighbors and of trade in kind, they are ill-equipped to function with the common denominator of money and ownership. The cart has become a relic, yet its presence defines the space as it did before, essentially a pinned down version of the roadside settlements. Still occupying the in-between land, this time between buildings rather than road and boundary wall, carts stand at the back of the site, anchoring the storage, while wide verandahs approach the path, and a chula (stove), helped by a blower, which is cemented into the finished floor. Walls and columns replace tent stakes and IPS (Indian Patent Stone, or poured cement floor) replaces packed earth plinths.

[cart as identity]

The draw of the city and the push of the urban slowly strips away everything but the memory—of who they are, where they are from, and what they once did. The response to this loss is manifested in the exaggerated position of puja on the cart. What once occupied a small, protected opening on the cart body, now extends onto the shaft, across the surface and even off the cart into whole room installations. As they move further from the continuous journey, and are drawn into the apparent permanence of urbanity, the symbolism of the element that once carried them grows stronger, a relic—gaadu—and a name—gaduliya—necessary to define their identity as they slip into the life of the city.