Ranchhodpura, Gujarat 2010 - 2015

In many ways, this project is more about its making than anything else. For us, an opportunity to reflect on the contingencies of the design process—where they happen and how, at what scales they interact, and which points we must fix to let others remain loose.

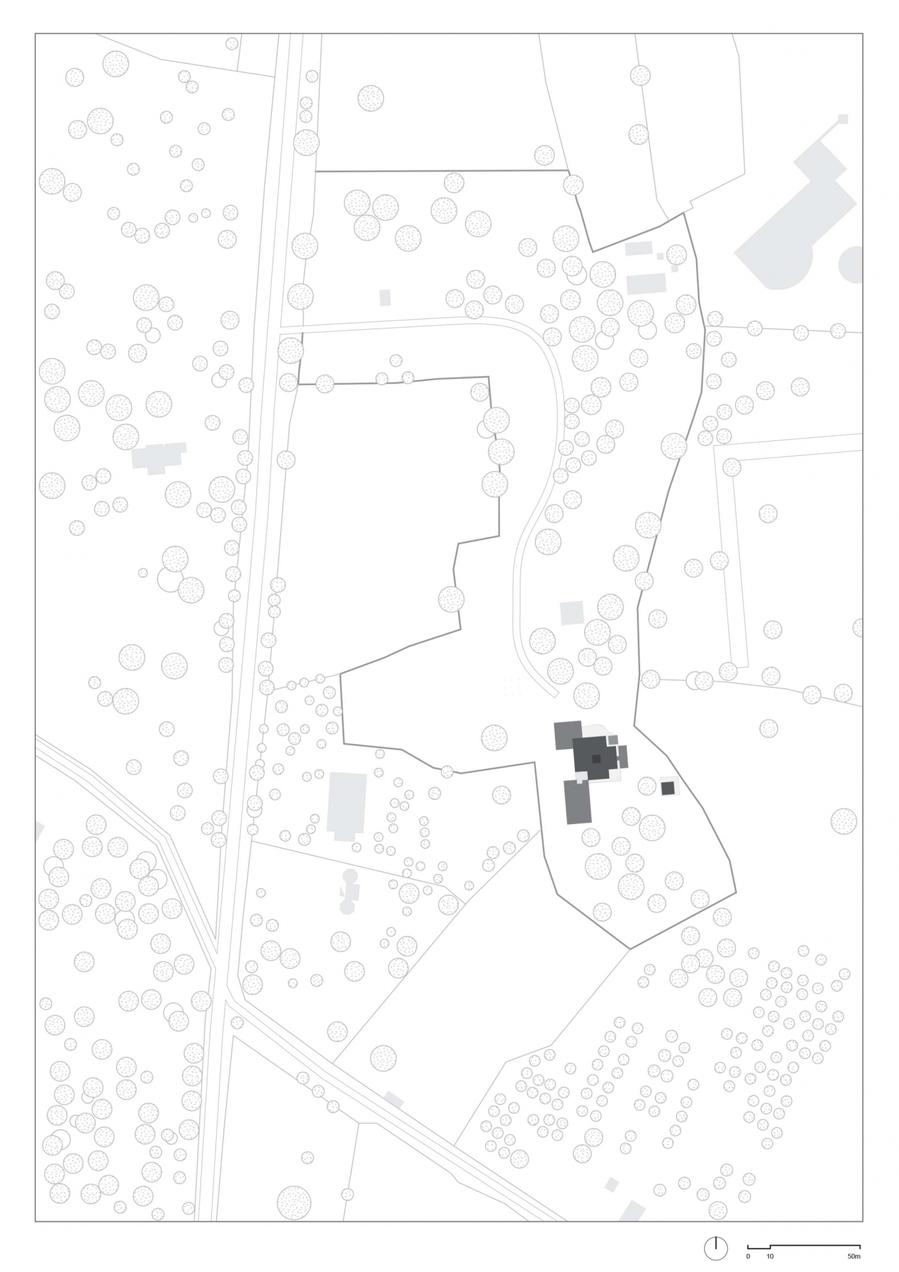

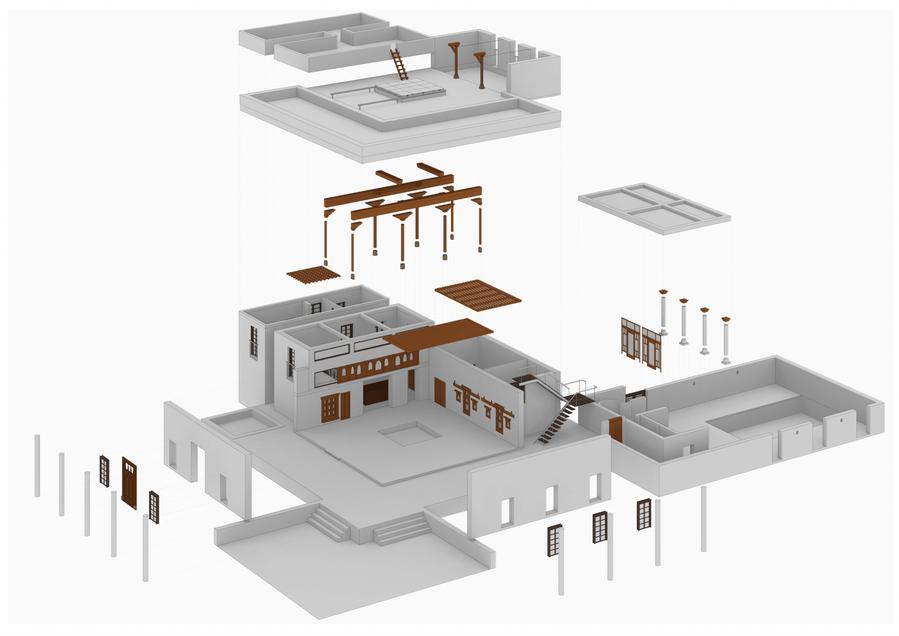

The house in the landscape was recreated from the pieces of a 300 year oldhaveli. In this structure we merge new and old systems of assembly, combining 18 inch brick walls in concrete frame with gutai lime plaster and restored telpaanifinished teakwood elements. The basic form follows the original courtyard layout, flanked by bedroom, kitchen and mezzanine, while the wrapping terrace and sunken entry extend into the spaces outside, to transform the original row house layout into a part of the landscape.

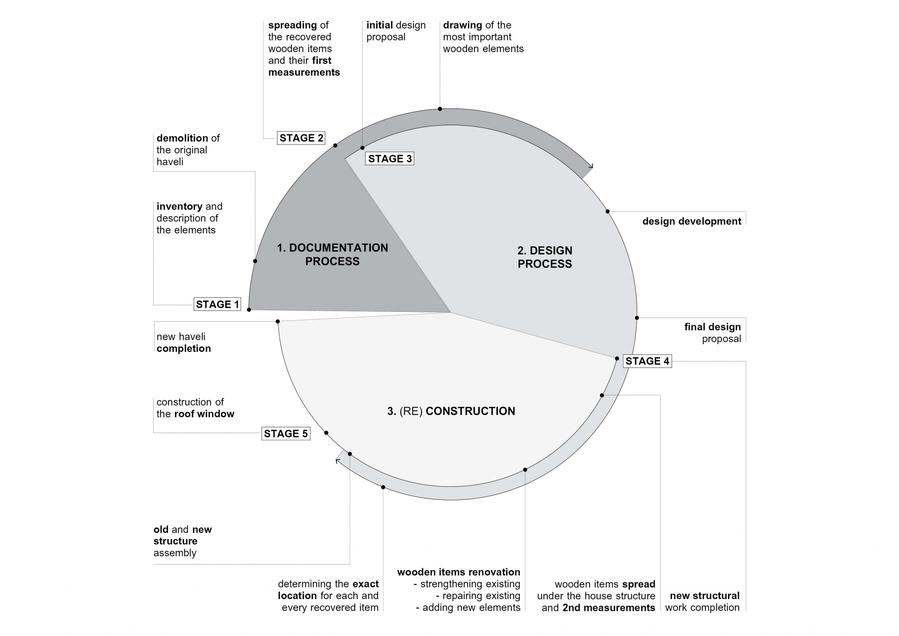

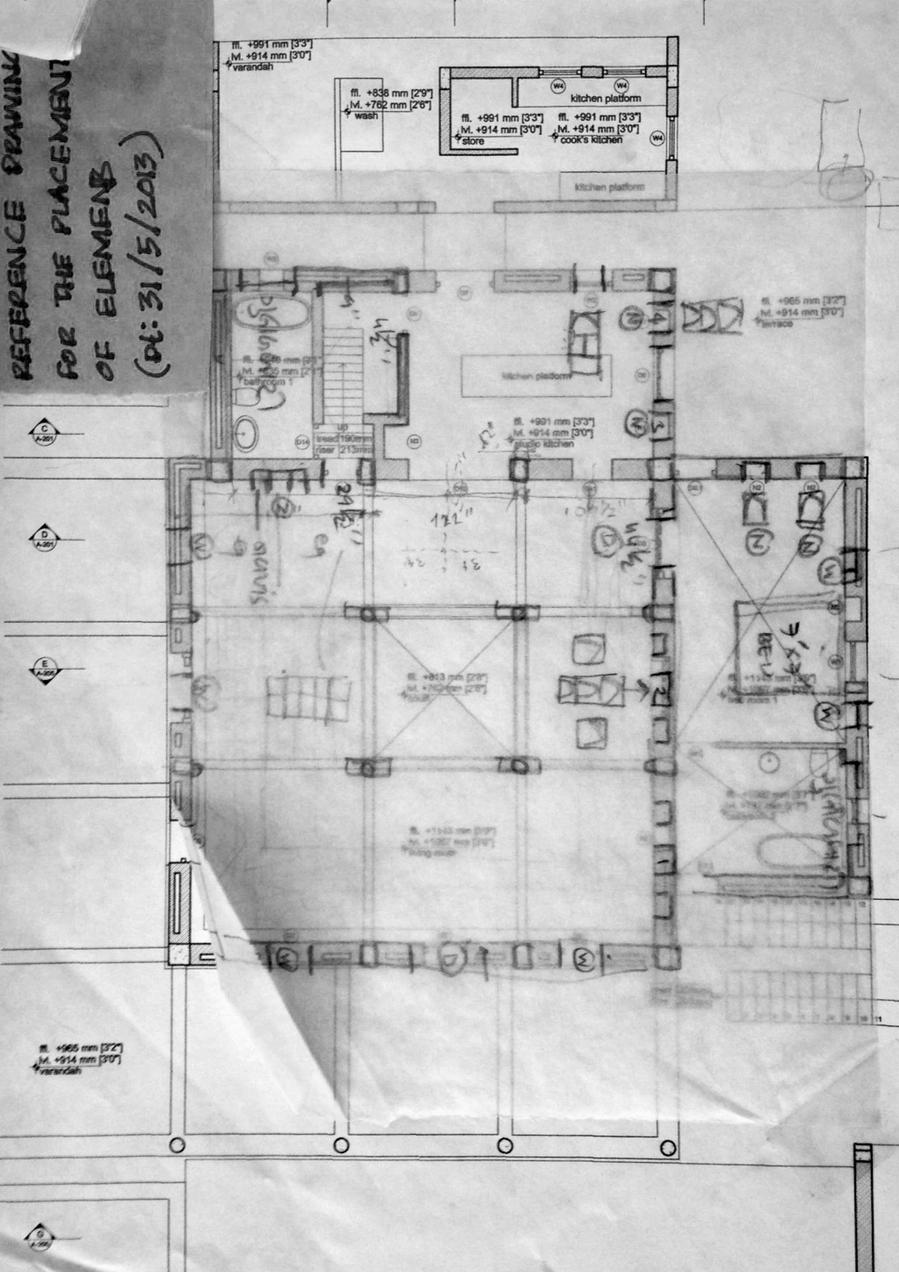

The process began with a video, taken by an owner ready to demolish a termite damaged but beautiful row house in northern Gujarat. Normally when this type of house is destroyed its parts of value are sold to various antique dealers. Instead, our client acquired the entire house, packed up all its parts, and stored them on his property near Ahmedabad. We began the conceptual design process with the video and a short list of elements with their basic dimensions. Only after agreeing on the direction of the design did we take one day (because we couldn’t risk the damage or theft associated with leaving elements out all night) to unpack as much as we could and measure critical dimensions. Already there we found many pieces not present in the list, and barely covered in the imagery. From those basic measurements we drew up the elements and developed the design. The first time we could completely open the elements and start to puzzle them out came after the columns, roof and plinth were finished. It was then that we began the conversations with our carpenters about what, where and how, given the basic framework of the courtyard we had seen and planned. As elements were unearthed, projected locations shifted to accommodate new pieces, or to hold related parts. We gradually moved away from drawings, making more decisions on site, because the argument couldn’t be divorced from the place and the artisan’s perspective.

Here the logic of new and old coming together was reflected in the process by which they were made. Old elements needed conversations, placements, and at most, hand drawings. Their unique form and dissimilarities rendered digital drawings complicated and unnecessary, while the new elements, inserted alongside old in the structure, were designed, drawn and executed according to a more typical practice of construction drawings and site checks. These parallel processes resulted in an intensely site driven design, which evolved as much during its process of construction as during its so-called design phase.